SmartAis App for the Blind: LiDAR Scanner + AI = Acoustic Hazard Detection

I feel my white cane tip gliding over the cobblestones. But I’m not actually blind – I’m artificially blind for just a few minutes.

Under my sleep mask, the traffic roars as if I’m standing in the middle of a busy intersection. The sounds I can easily sort as a sighted person suddenly turn into a threatening wall of noise.

I know someone is standing next to me, I know I won’t get run over – but my body believes something else. In that moment, I understand for the first time on a physical level what it’s like when a white cane can scan the ground, but can’t warn you about what suddenly appears at hip height.

This experience makes it very clear how important targeted support is for blind and visually impaired people in everyday life.

Out of exactly this feeling came what I want to talk about here: a system that is not meant to guide blind people like a satnav, but to warn them precisely at the points where their white cane reaches its limits.

The development of this system was a direct response to the everyday challenges blind and visually impaired people face.

Why

The real stumbling block

When a Munich-based startup approached me, they brought what sounded like a simple question. They wanted to know what the biggest tripping hazard is for blind people in everyday life. My first spontaneous answer was curbs or uneven paving. But the reality is different.

The white cane is very good at scanning the ground. Irregularities, edges, and small obstacles on the path can be detected surprisingly well.

For everyday navigation, however, safe routes and reliable connections are especially important, so that blind and visually impaired people can orient themselves independently and safely.

The biggest problem is everything that’s higher up. E-scooters lying across the pavement, truck loading ramps, unmarked bollards, branches sticking out into the way. All of these obstacles are exactly in the area the cane often doesn’t detect – but that is very painful for the body.

Blind people develop fixed routes that they walk again and again. On these routes, they know every corner, every traffic light, every curb. Especially at street intersections, navigation becomes a major challenge, because this is where many unexpected obstacles and changes appear.

It only becomes truly dangerous when something changes along these familiar routes. When there was no e-scooter there yesterday, but today it’s lying right across the path. That’s where falls, injuries, and insecurity arise.

What already exists

I took a closer look at the tools that already exist. Most people know tactile guidance systems from train stations. Longitudinal grooves in the floor act like rails, and dotted fields mark junctions or crossings.

With a white cane, these patterns can be felt very well. They allow blind people to be guided reliably to traffic lights or platforms.

Acoustic traffic lights are another example. A quiet ticking signal indicates that there is a crossing here. When the light turns green, the signal switches to a faster rhythm.

Under the push button, there’s a small arrow you can feel with your hand. It shows which direction the street runs, even if it’s at an angle.

All of these systems are great aids. But they are firmly embedded in the infrastructure. As a supplement to these traditional assistance systems, modern technologies such as barcodes, QR codes, and digital maps offer innovative ways to further improve orientation and participation for blind and visually impaired people.

Special GPS apps and navigation apps with a wide range of features – such as voice output, environment descriptions, and accessible routing – provide additional benefits and increase independence and safety in everyday life. But they know nothing about the e-scooter someone carelessly dumped on the path this morning. That’s exactly where our joint idea came in. We didn’t want to replace anything – we wanted to close a gap.

How

The idea with LiDAR

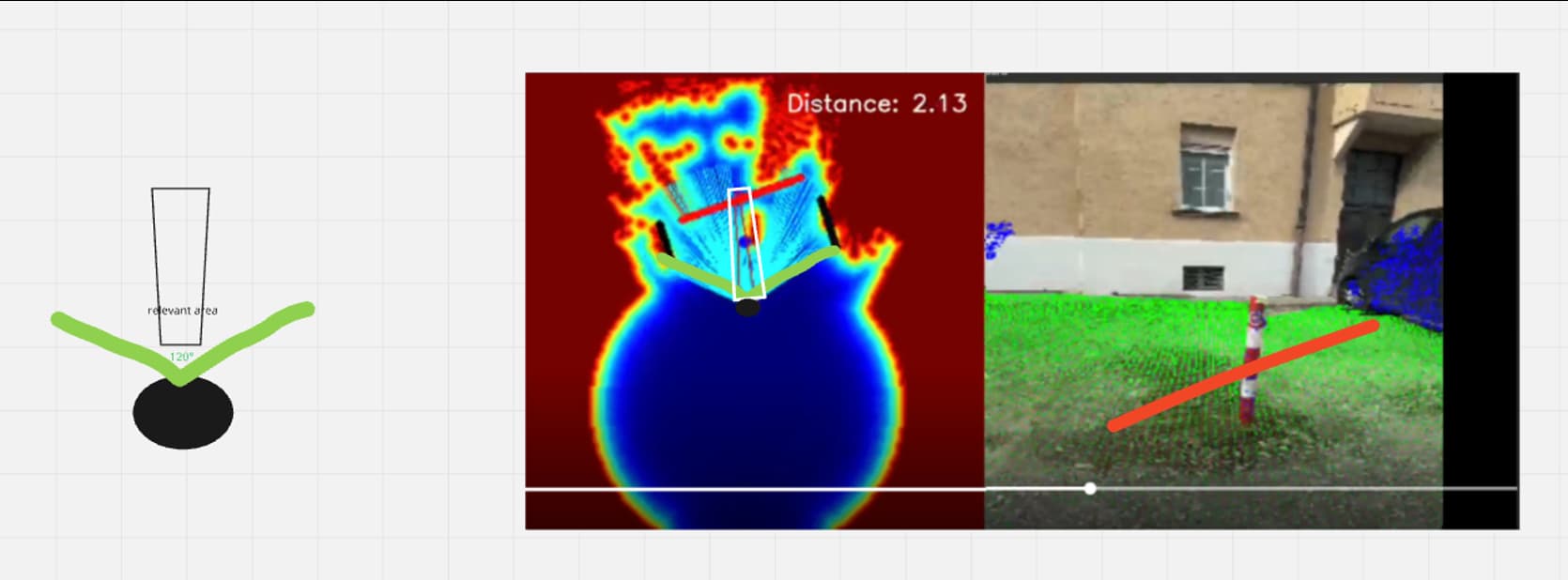

The startup was already quite far along when they came to me. They had built an app that uses the LiDAR scanner in modern smartphones. This sensor sits next to the camera in the iPhone and sends invisible light pulses into the environment. From the time it takes the reflections to return, the system calculates the distance to objects. A simple depth map is created.

Development of the app is based on modern artificial intelligence and advanced programming, enabling innovative technologies for object detection and navigation.

In addition, photo and text recognition are integrated, so users can take or upload photos and have their contents automatically analyzed and described. The “My AI” feature extends the app with AI-based assistance that describes images and situations for visually impaired people.

On the smartphone, it looks like this: the camera image is displayed, and a color overlay is placed on top of it. Everything recognized as floor is green. Walls or obstacles appear in other colors. Even e-scooters can be detected as their own shape.

My task was to turn this visual analysis into a meaningful audio system – something that supports blind people in everyday life without overwhelming or confusing them.

Guide or warn

First, I observed how blind people orient themselves with a guide dog and with a cane. A guide dog actively leads. You are meant to literally follow the dog’s movements. The dog makes sure you don’t walk into obstacles.

The white cane works the other way around. It wants you to bump into the obstacle – but early enough and in a controlled way. Only through this contact do you understand where something is blocking your way.

Translated into audio, that means: either I build a system you follow like a dog, or I build a system that warns about dangers like the cane.

We explored both ideas. A sound you follow is tempting. You know that concept from video games. In a racing game, a tone tells you when to brake or steer.

Out on a real street with unpredictable obstacles, however, things get tricky. As soon as a system actively dictates the path, it implies a sort of liability promise.

If I pull someone to the right with a sound, and there’s actually a road instead of a sidewalk, that can become life-threatening in the worst case. We wanted to be very careful about that.

That’s why we chose the white cane principle. The system should not say where to go. It should only say where something is in the way.

For navigation, acoustic instructions and clear voice output are used to guide blind and visually impaired people safely.

In addition, the app offers various functions: displaying relevant points of interest, marking routes, and connecting to other services in order to provide comprehensive and accessible navigation.

The relevant corridor

We define a narrow corridor directly in front of the person. It’s roughly as wide as the space you actually need when walking. The LiDAR scanner covers a much larger area, but most of that is irrelevant.

What matters is only what you could trip over in the next few steps.

As soon as an obstacle appears in this corridor, the system places a sound source there. Rough localization is enough. “In front,” “front left,” or “front right” is completely sufficient for most users.

Super precise angles like 37 degrees cause more confusion than clarity.

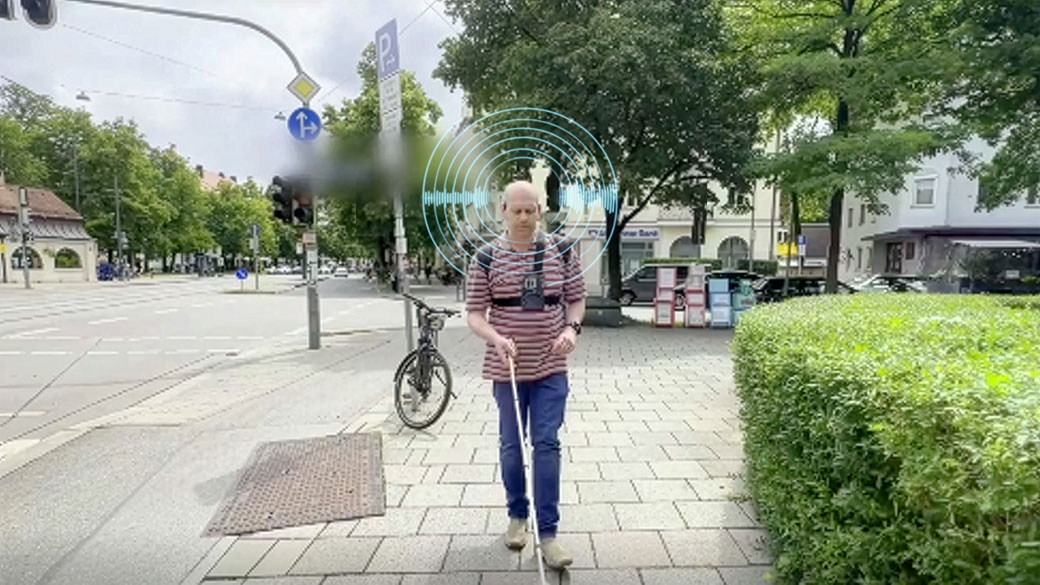

The smartphone is carried in a chest mount, slightly tilted downward. This way, the sensor sees the ground and the first hip-level heights well. Headphones are connected via Bluetooth. In many tests, we found that bone conduction headphones are a good solution.

The ears remain open, the environment stays audible. The sound quality is limited, but in this case, intelligibility of the signal is far more important.

Especially for blind and visually impaired people, this app makes an important contribution to mobility, because it supports independent orientation and safe movement in everyday life.

Sound instead of high-tech show

The first question many people ask me is whether the sound is binaural and super three-dimensional. The answer is very deliberately no. I love 3D sound, but here function comes before effects.

More important was finding a tone that is clearly understood as a warning signal. It shouldn’t sound too much like existing acoustic systems. A sound that resembles a traffic light would be confusing. A continuous tone like a car reversing alert would be too aggressive in the long run.

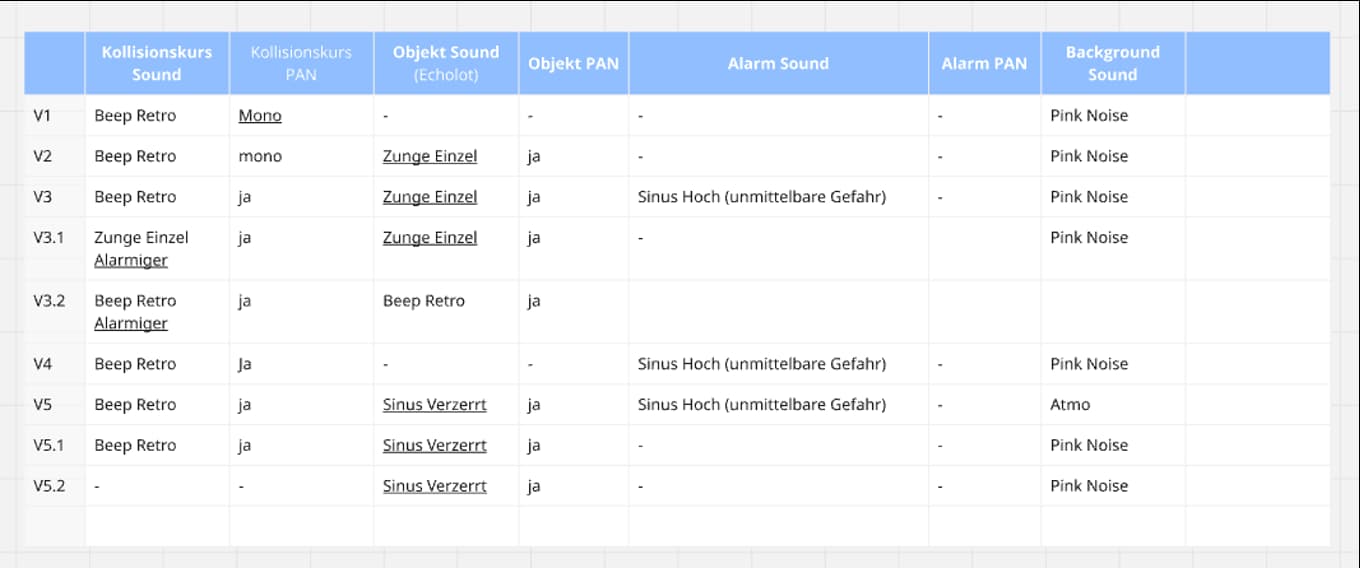

Together with my team, I created different sounds: subtle clicks, synthetic beeps, and sounds that are a bit like sonar. We tested these variations with blind users.

In the end, a mix of pop and click won out. The sound feels organic, stands out clearly from street noise, and doesn’t get annoying too quickly.

A clear advantage of this sound is that it makes operation easier for visually impaired users and improves acoustic orientation. However, in certain noisy environments there can still be challenges in clearly distinguishing the signal.

What

How the system works in everyday life with accessibility

In everyday life, the system runs on a smartphone in a chest harness. The person still uses their white cane – that remains the most important tool. The app is an additional assistance system.

Some of the app’s key features include voice output for environmental information, acoustic instructions for navigation, the presentation and audio feedback of relevant points such as points of interest, detection and representation of routes, and connectivity with other services and navigation systems.

While the person walks along their usual route, the LiDAR scanner continuously analyzes the area ahead. The algorithm decides whether an object lies within the relevant corridor and whether it poses a tripping or collision risk.

If it does, the warning sound plays from the direction of the obstacle. In addition, the system not only detects obstacles but also other relevant objects and points them out acoustically. Through different audio signals, what is happening in the surroundings is conveyed, so users are always informed about important events.

The system can also be used specifically to search for certain objects or cues, supporting orientation and reaching a destination. Once the object leaves the corridor, the sound stops.

For stairs or significant height differences, we developed a dedicated sound. Many blind people can cope well with stairs as soon as they know they are there. The special tone signals that there’s a drop coming up. This way, they can adjust their movement before reaching the edge.

Outdoor spaces first

At the moment, the system is primarily intended for outdoor use. Indoor spaces are very complex: full of furniture, narrow passages, and constantly changing objects. Outside on sidewalks, the scenario is clearer.

Many blind and visually impaired people already use GPS apps such as Google Maps, BlindSquare, and other navigation apps together with digital maps to improve their mobility and independence and to orient themselves better along routes and at intersections. The app described here is designed to complement these technologies in a meaningful way.

The actual goal is to report changes, not to accompany every step. When a path is clear, the app remains silent. It only speaks up when something new appears in the way.

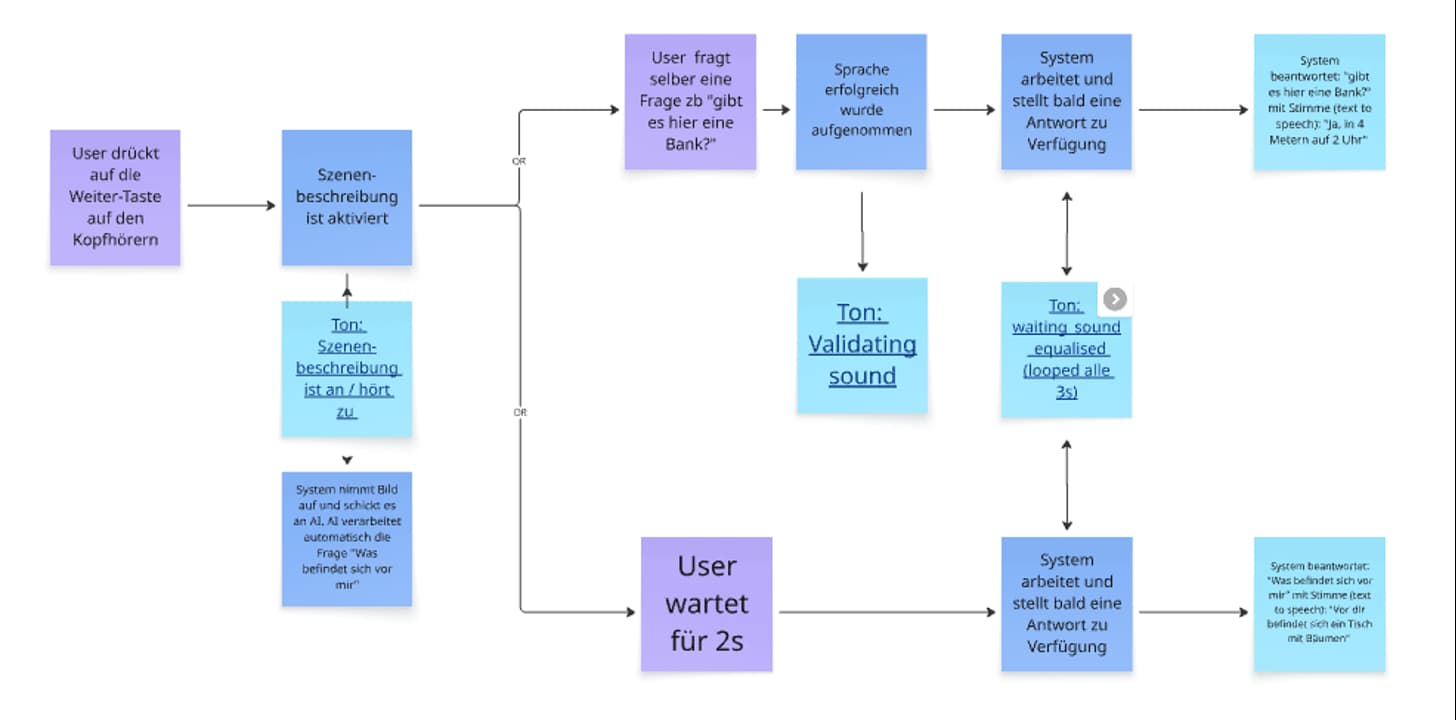

Image description on demand in audio games

Another building block is the ability to request a description of the surroundings on demand. Modern technologies such as Be My Eyes, Be My AI, My AI, and Seeing AI use artificial intelligence to provide both photo and text recognition and thus help blind and visually impaired people in everyday life. By pressing a button on the headphones, the person triggers the smartphone camera.

The photo is sent to an AI system, which turns the scene into a text description. That text is then converted into speech and played back through the headphones.

This way, I can, for example, have it tell me that there’s a street in front of me, a bench to the left, or a building with an entrance to the right. This feature is not meant for every second, but for moments when you deliberately want more context. It complements the short acoustic warning signals with a verbal layer when needed.

Outlook

For the future, I see many possibilities. New developments and advanced technologies – such as AI-based navigation and smart assistance systems – will continue to improve daily life for blind and visually impaired people.

Headphones with intelligent noise cancellation could amplify warning signals from cars and dampen unnecessary noise. Head tracking could help make the soundscape feel even more natural. It would also be exciting to use data from external systems. E-scooters usually know their exact location.

If such information were accessible, potential hazards could be taken into account before the LiDAR scanner even sees them.

The app is designed as a supplement to existing aids such as guide dogs or long canes and aims to further improve navigation and safety.

The market for innovative solutions is growing steadily, and technologies like this are becoming increasingly available worldwide to support people with visual impairments all over the globe.

Despite all these visions, the core of the project remains very simple: I want blind people to feel a bit safer when walking their familiar routes.

It’s not about taking control away from them. Quite the opposite. The system is meant to help them stay independent. A small click in the right moment can make exactly that possible

This button links to my contact details