AJO – A 3D Audio Only Game Escape Room

I’m sitting in the studio, putting on headphones and switching the image off. No monitor, no game graphics, just black. In front of me I hear footsteps on gravel, rustling fabric, drops falling from a ceiling. A voice asks quietly, almost nervously: So… which way now? In that moment it becomes clear: this game exists only in my head and in my ears.

That’s exactly what this project is about. A game that does without images and instead tells everything entirely through sound. The player character is called AJO. I never see her. But I hear what she hears. I follow her through caves, tunnels and tight spaces, relying on just one medium: spatial audio.

The project shows how innovative audio technologies can enrich the everyday lives of blind and visually impaired people and strengthen their independence through immersive sound worlds.

Why

A game without visuals

The goal was radical from the very beginning. I wanted to help build a game that works completely without a visual layer. No interface, no icons, no menus. Just audio. Sound as navigation, as information, as emotion.

It made sense to look at audio games for inspiration – games where sound is not just decoration, but the central gameplay mechanic.

At the same time, I wanted to go beyond the classic understanding. I wasn’t interested in simple audio dramas with choice options, but in a real spatial game that I build in an engine, where every movement in space is also tangible in sound.

Among the game’s special features is the deliberate use of different audio elements that allow players to solve tasks, support navigation, and maintain orientation in the environment using sound alone.

One question was at the core of everything: is spatial sound on its own enough to convey orientation, tension, and a coherent story? Or do we lack too many anchor points without images?

AJO as focus character

To make that tangible, we needed a clear narrative perspective. That’s how AJO came into being. She is the protagonist moving through a dark world. As the player, I see nothing. I’m on a call with her, hearing what comes through her headset and giving instructions. She acts, I interpret.

The basic idea was that AJO is moving in complete darkness and can only progress through her acoustic perception and my decisions. We wanted a proof of concept showing that a narrative experience can be built entirely on spatial audio perception.

Spoken dialogue is used deliberately to pass on information and instructions to players, enabling accessible, audio-only navigation through the game world.

Inspiration from the games world

One of the triggers was the game Horizon Zero Dawn. There’s a feature called Focus. When you activate it, the sound world changes. Sounds of clues and dangers move to the foreground. You suddenly hear more clearly where enemies are or where an important point is located.

I asked myself how such a focus could be translated into a pure audio experience. What happens if I push that idea further and completely remove the image? Can I navigate through a world with something like an acoustic sonar?

Purposefully placed acoustic signals can support orientation and navigation by conveying important information about the surroundings and potential obstacles.

How

Iterative development in the engine

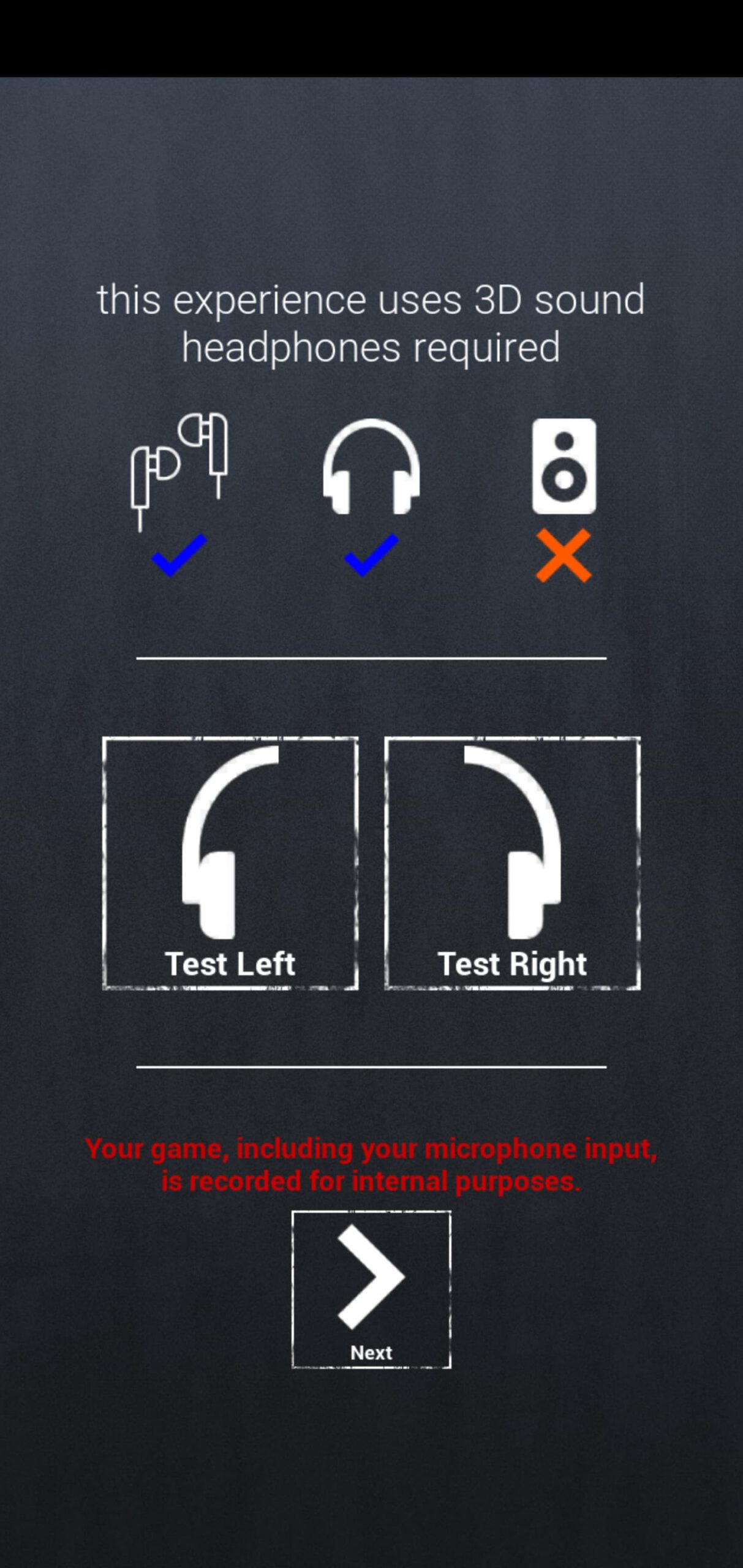

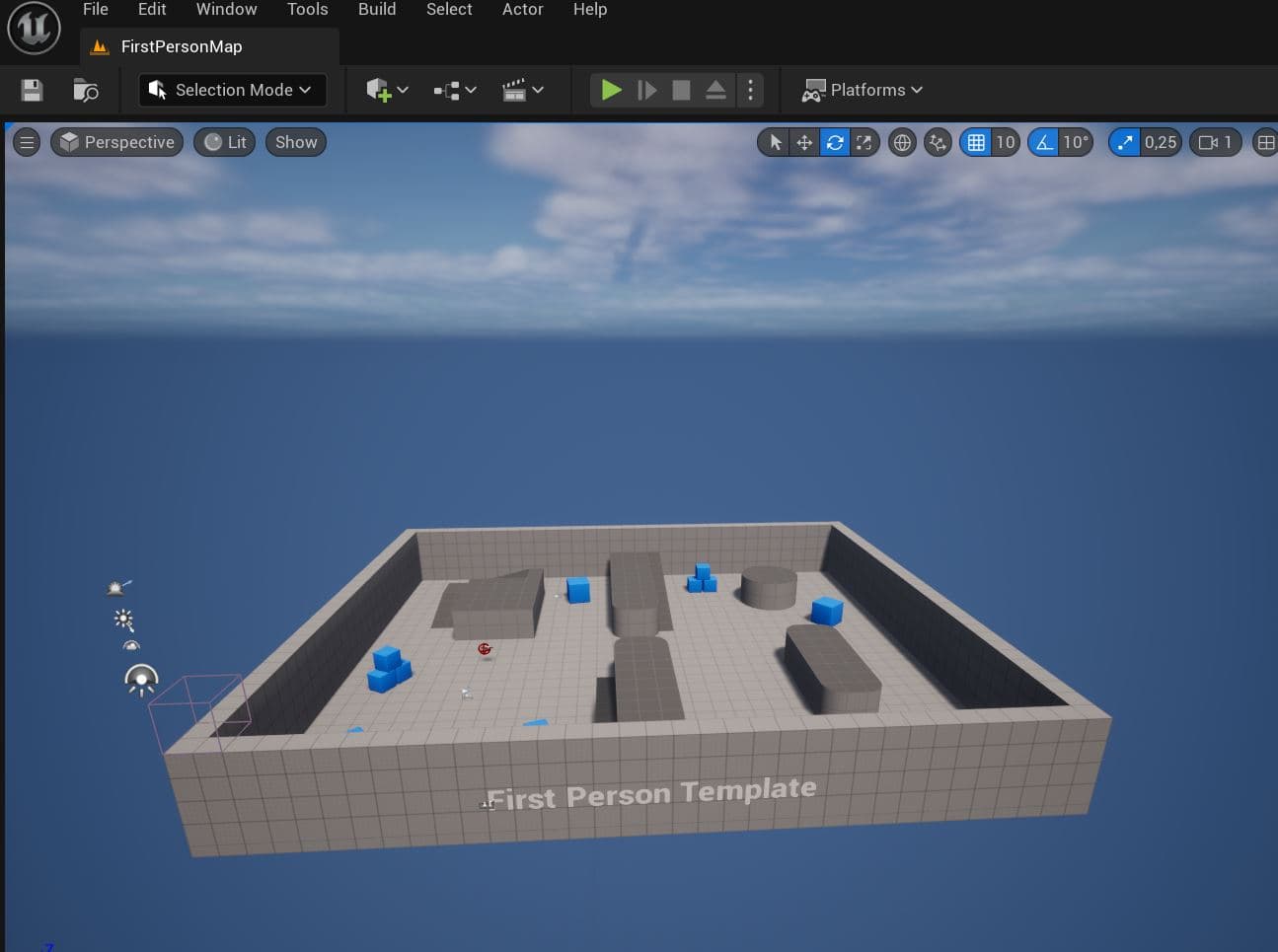

Implementation happened directly in Unreal. From the start of development, modern technologies were used in a targeted way to improve support and accessibility for people with visual impairments. I worked with the developers in sprints, constantly testing, discarding, simplifying, and rebuilding. From day one it was clear: sound must not just be beautiful here. It has to work.

The audio pipeline consisted of several building blocks: binaural or ambisonic spatial audio for 3D mapping, interactive sonar sounds for active navigation, Foley for footsteps, clothing and objects.

Ambiences for different rooms. Music to set emotional accents in a targeted way, but not as an endless loop. And voice-overs for AJO and other characters who provide hints and carry the story.

Every sound was given a task. It had to convey direction. It had to make distance perceptible through loudness and frequency. It had to suggest materials and room size.

Does the step sound like metal or gravel? Is the room dry or reverberant? All of this had to be “readable” in the sound.

Phase 1: Orientation without visuals

In phase 1, we chose a very reduced setup. A small course in the engine, a few objects – for example, a dripping tap, a humming fuse box, a bird acting as an acoustic landmark.

Control was initially handled through a simple interface: forward, back, left, right. The character moved through the world in steps. The idea: I hear a sound, move towards it, the sound gets louder, the direction clearer, I trigger an action and the story continues.

Acoustic points like intersections or other distinctive locations served as orientation aids in the game, helping players to perceive important spots in the environment more deliberately.

There was also a sonar. If I didn’t know how to proceed, I could trigger a kind of acoustic ping.

The engine then played short hints for relevant objects so I could locate them in the first place. The idea was that players would gradually build up acoustic maps in their heads.

Reality was much more complicated. Localization worked in principle, but only with very clear directional differences: straight ahead, clearly left, clearly right. Anything in between was difficult.

A 45-degree turn was too subtle. Players often didn’t know whether a sound was still half-left or already in front.

Then there were effects such as occlusion. When an object was behind a wall, it was damped and seemed to come from a different direction than expected. That’s physically plausible, but cognitively hard to decode when you have no visual reference.

Some sources remained unfound despite sonar. The bird’s nest stayed acoustically invisible. The water was splashing, but not clearly enough to walk towards it in a targeted way.

Without pronounced reverb, spatial context was also missing. It was hard to tell whether I was close to a wall or standing in the middle of a room. On top of that, several simultaneous sounds quickly became overwhelming.

If the sonar output three hints at once, it was unclear where to start. Navigation was possible in principle, but exhausting and slow.

Phase 2: Clearer rooms, clearer logic

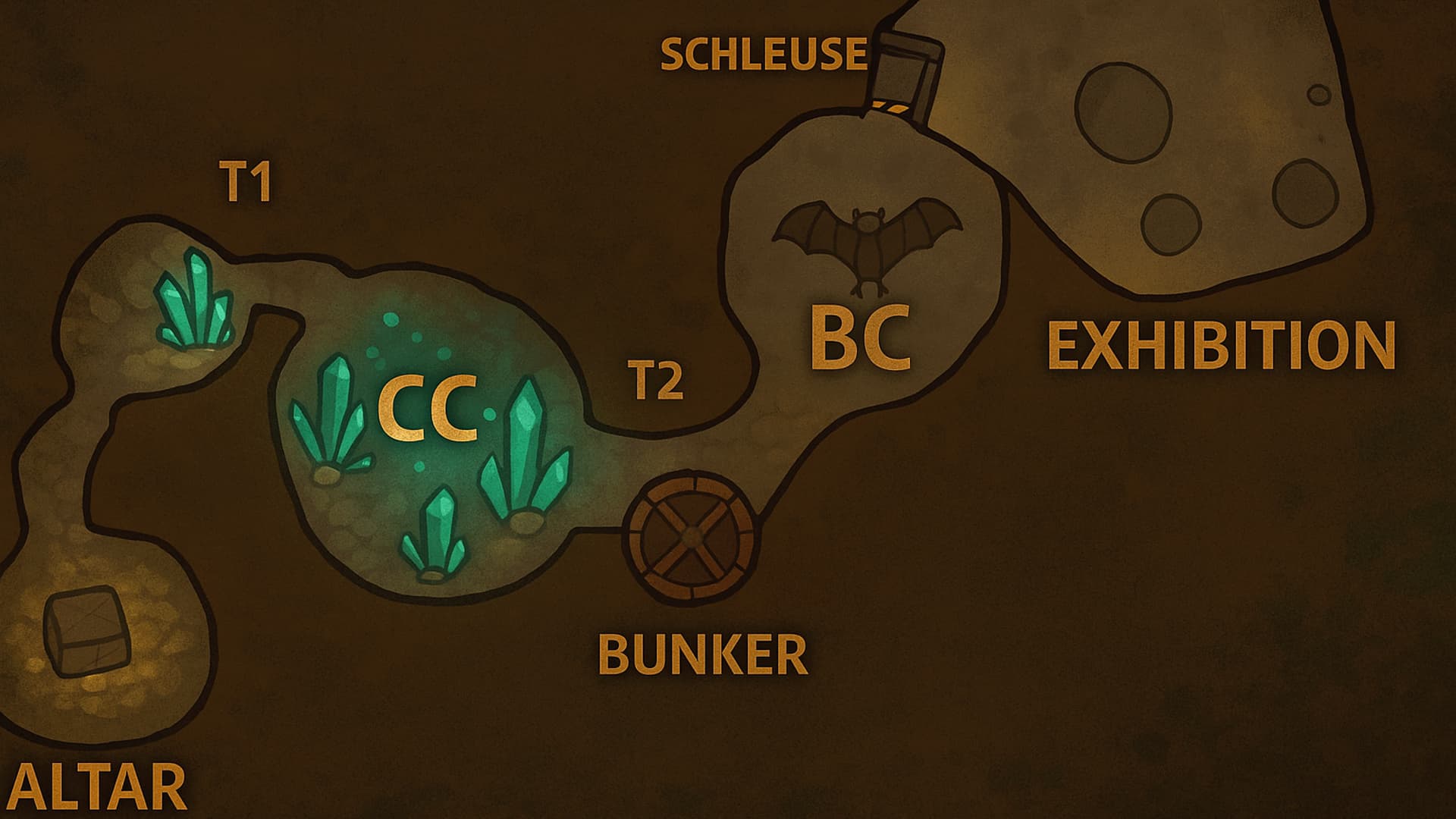

From these insights, I developed phase 2. Instead of an abstract course, a small game world with clearly separated rooms emerged. A crystal cave. A tunnel. A bunker entrance with a door and cables. An airlock with machines and pressure sounds. A bat cave where enemies react to noises. An exhibition space that serves as the starting scene.

The acoustic design of the environment plays a major role in helping users orient themselves and recognize their position in the room.

Each room received a clear acoustic profile. In the crystal cave, resonant tones are ringing. In the tunnel, tight reflections dominate. In the airlock, you hear jets of water and heavy machinery. Just from the base ambience, you can roughly tell where you are.

Interaction was simplified. Doors, switches and objects were given distinct acoustic states. A closed door sounds different from an open one. A cable hum signals electricity.

When I trigger a sonar ping now, I only get one hint at a time, no longer several at once. The game world responds almost chronologically.

Technically, I made reverb and occlusion more pronounced. Wall reflections are no longer a subtle aesthetic effect, but a clear signal.

Muffled sound means “behind the wall”. Clear sound means “free in the room”. Different materials received their own sonic colors. Metal sounds different than wood or stone.

I also changed the directional resolution. Instead of rigid steps at coarse angles, I use finer movements or automatic focusing on relevant objects.

The goal is not to represent every single degree. The goal is for the player’s brain to understand: There’s something important in front of me.

AI in the background

Another step in phase 2 was connecting to a language model. Player inputs are sent to a language model that interprets the current game state.

Thanks to the advanced intelligence of AI, the system can support users in a targeted way by recognizing complex situations and providing appropriate assistance. The responses are converted to speech and positioned in the 3D space.

This allows AJO to answer questions such as: What do you see in this room? Or: Is there anything here I can use?

The engine checks which objects are visible or active, formulates an answer, and outputs it through AJO’s voice.

At first, this approach felt almost over the top. But the longer I worked with purely audio-based navigation, the clearer it became: without these hints, a lot simply remains incomprehensible.

The combination of spatial sound design and context-based spoken hints makes the experience far more accessible and reduces the pure trial-and-error component.

What

The role of the players

In the finished prototype, players are on a call with AJO. Through their headset, they hear what she hears. They themselves are not present in the world, but act more like operators in the background.

They provide guidance; AJO executes it. In doing so, players actively support AJO in solving tasks, helping her tackle everyday challenges.

Communication happens through voice, sounds, and sonar. Players listen, draw conclusions, and give instructions. AJO comments, doubts, reacts. A relationship emerges that works entirely without visuals.

Rooms as acoustic scenes

The game world consists of several clearly separated scenes. At the altar, AJO finds an artifact that triggers the story. In the first tunnel, basic navigation is tested.

In the crystal cave, resonant stones serve as acoustic landmarks. At the bunker door, a puzzle emerges from cable hums, metal sounds, and sonar hints. In the bat cave, enemies react to noise, reinforcing loudness as a gameplay element.

In the airlock, water, pressure, and machinery meet. At the end, in the exhibition, AJO encounters a system that seems to recognize her.

Each room consists of multiple audio layers: ambience distributed in six degrees of freedom in Unreal, sonar interactions that make objects and states audible,

Foley for all movements and actions, dialogue for AJO and supporting characters, and music used only selectively as a dramatic amplifier. The various audio layers deliberately convey information about the environment and the current situation to support orientation and understanding of the acoustic scene.

Challenges

The biggest challenge was that orientation through sound alone only works if every sound carries clear information. There can be almost no acoustic ballast.

Everything you hear has to contribute either to mood or orientation – ideally to both. In developing acoustic orientation, specific issues emerged, such as how to convey directional information and distance clearly and understandably without overwhelming the user.

Since no head tracking was used, I had to convey direction through other means: sonar samples, volume curves, filters, reverb, and timing. Distance and position had to be readable through these parameters, without overloading the brain.

On top of that, storytelling and gameplay had to support each other. There is no moment where graphics can jump in to explain something. If a door is open, you have to hear it. If a puzzle is solved, the soundscape has to change.

Another important aspect was the structure of the audio pipeline. With hundreds of sound objects, spontaneous naming is not enough.

Clear naming conventions, clean folder structures, and modular setups were essential to iterate as a team without losing track.

Conclusion

The prototype shows that complex spatial presence, tension, and an entire story can be built using audio alone. Navigation without visuals is possible if sound design is consistently approached as functional.

For me personally, this project was a kind of lab. A place where I could test how far I can go with sound when I hand over full responsibility to it. The answers are not always comfortable. Many things are more cognitively demanding than we’re used to. But that’s exactly what makes it exciting.

The strengths of this project lie particularly in giving blind and visually impaired people barrier-free access to immersive media and offering them new, independent experiences.

Back to the blog